Projection Protests: A How-To Guide

Part I: Choosing targets

Good Afternoon:

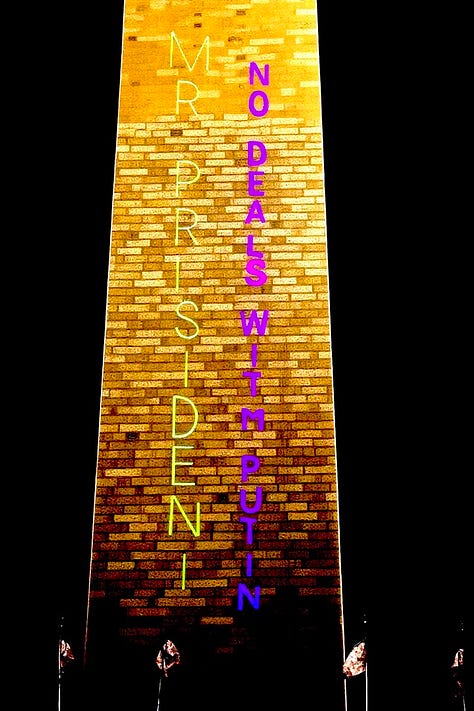

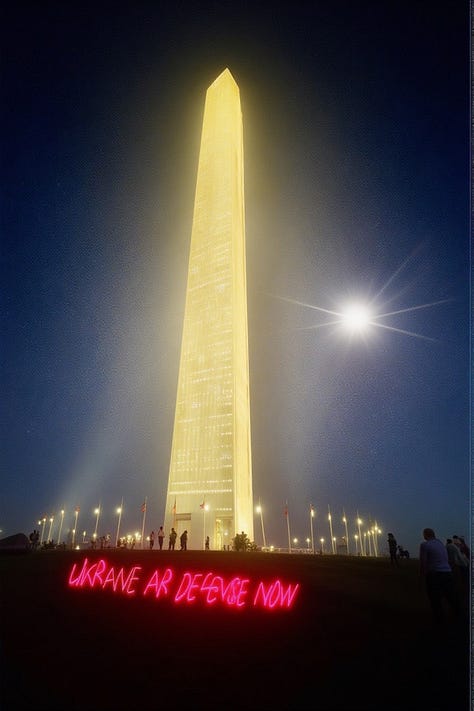

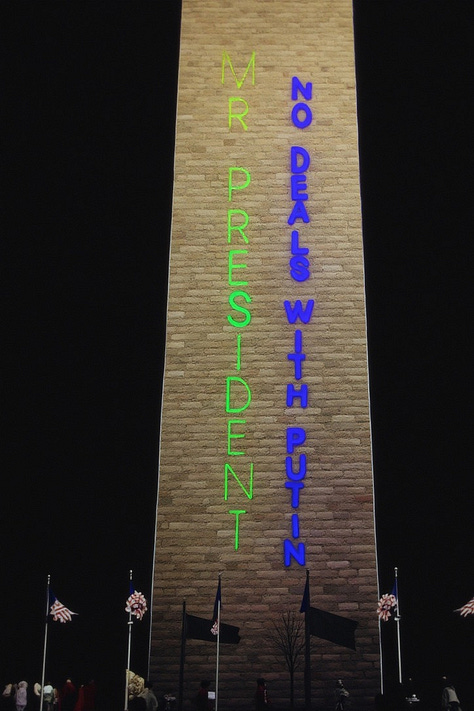

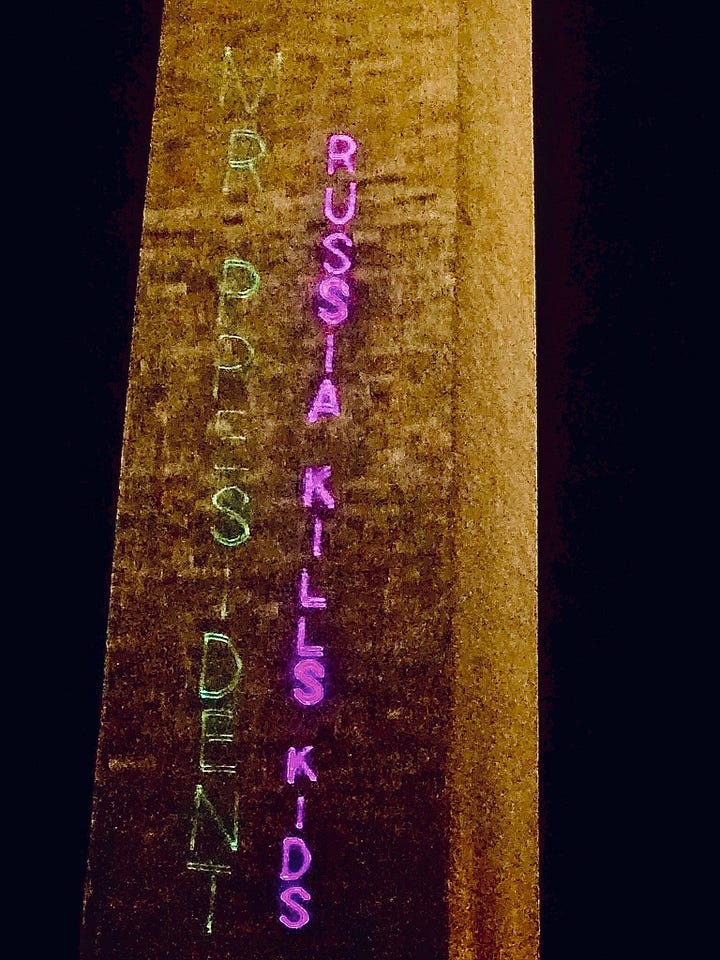

Over the weekend, I got angry because of the news of the Alaska summit and President Trump’s renewed interest in demanding land concessions from Ukraine. So I released these images of my projection protest in early July—the one that resulted in police seizure of #LordLaser and #LadyLaser and has landed me a mandatory court date at some time in the indeterminate future.

The response on social media has been frankly breathtaking and has brought tears to my eyes more than once. Nikita Titov—the Ukrainian artist whose work I projected on the Russian embassy and who did my portrait some time back—made an image out of my name (see below). I have received lovely notes from Ukrainians all over the world—most movingly in my own community. I have received lots of tweets on Bluesky from people who want to help fund replacing the equipment and help pay my legal bills. (Answer: no, you can’t pay for my toys or for the wages of my sins, except by becoming a paid subscriber to #DogShirtDaily.)

Perhaps most movingly of all, I have received any number of requests to write up how others can get in the laser-protest action:

There have also been images of operations that people have done which they tell me my projections helped inspire. Some are in support of Ukraine. Some are in response to the Situation domestically:

I am deeply moved.

I take the charge to help and inspire others get in on thoughtful, high-impact, theatrical, non-violent protests very seriously, and a how-to guide about using lasers for those protests seems like a very good way to help people get started. So I am going to spend each day this week writing a bit of an everything-you-wanted-to-know guide about projection protests.

The first principle of of this type of guerrilla protesting is Just Try It. I want to emphasize that none of the expertise I now have in this area—zero—was stuff I was born with or flowed from my previous professional experience. It is all stuff I learned by trying things and seeing what got attention, what did and did not provoke police to intervene, what did and didn’t move people. We are not talking here about assholeish activity that hurts anyone. We are not talking about anything destructive. We’re not talking about anything that should morally embarrass the participants and thus needs to be done covertly or with shame. So if you have an idea, try it. And if it doesn’t work, fine. Do something differently the next time.

One of my early Special Military Operations was against the Russian embassy press office, which has its own building in Washington right near my office. I had the very bright idea—I thought it was bright, anyway—of taking a giant projector (22,000 lumens giant), which I dubbed the Big Ass Projector (BAP), and putting it right in front of the press office building and showing a movie, Mr. Jones—which is about the Holodomor—on the side of the building.

A lot of people turned up for movie night that night. The film’s direector—the great Agnieszka Holland, who is one of my cultural heroes—and its writer—Andrea Chalupa—both joined remotely for the livestream of the event.

And then the Russians parked a giant white van right in front of the BAP, which is too big to move easily, thus making movie night impossible. We improvised, and we brought in a mobile TV screen but the operation was not ultimately effective. And you know what? It was fine.

The people who had showed up actually gave me a big ovation when we shut it down with the movie barely one third over and mostly inaudible on a crowded street. You try stuff. Sometimes it works. Sometimes it doesn’t. You improvise. You learn. And you iterate. And then you do it again. Nobody will hold failure against you. You model the effort.

Notice the subject of those sentences. It is “you.” It is not “the projector.” I have made a game out of anthropomorphizing my projectors. They each get a name (the BAP, the LAP, Himar the Gobo Projector, #LordLaser and #LadyLaser). And I often write about them as though they had personalities:

But I try never to forget that they are mere tools. The actor here is me—and, more importantly, the people whose stories I am trying to highlight. That is true even though my image appears only occasionally in these operations. When you do one of these operations, you are the subject; you are the messenger; and you are responsible.

So let me start this series by laying out my general theory of projection protests. This theory does a lot to inform my sense of when these operations are appropriate and helpful and when they are not, when they are feasible and when they are not, and most importantly, how they can interact most usefully with other forms of protest.

A projection in and of itself is just a temporary billboard. As billboards go, in fact, it is not an especially good one. As I will explain in future parts of this series, they have real limitations in terms of how close the user has to be to the target, the conditions of the target, and the visibility and complexity of what one can project. By contrast, your garden variety electronic billboard has none of these problems.

A projector has exactly one advantage over a big screen—which is that most organizations you want to protest won’t let you hang a hostile billboard on their walls. By contrast, projection can be done involuntarily. You can turn their walls into your billboard.

It can be tricky for the targeted institution to prevent a projection—and trying, as the Russians have found out in attempting to counter my work on numerous occasions, can make the target look ridiculous and greatly amplify the impact of the protest. In other words, the advantage to projection protests is that they allow the protester to invade the physical space of the target in a fashion that would certainly be illegal if the protesters were using paint or spray cans but which has a different legal status (I’ll write more about the law of projection protests later in the week) when it involves photons only. Projections also permits access without trespass—sometimes over long distances—to walls that would otherwise be physically inaccessible.

In other words, the projection protest is at its most effective when the projector is transgressing a physical boundary that would otherwise make the protest impossible.

In my experience, laser protests are ineffective—boring even—in situations that do not have at least features of transgression. Putting up a generic political slogan on a building you have no reason to target generally doesn’t attract a lot of attention. I spent some time urging people to vote using lasers during the last election cycle; there was no surge of interest in these projections, even though they were kinda cool.

By contrast, project on a target against the determined will of the entity that it represents, and there’s a great story in that—not to mention the human drama of how the targeted entity responds. I learned this during the very first Special Military Operation, when the Russians tried to drown out our Ukrainian flag projection with a big spotlight of their own. The resulting video went viral and has been seen by many millions of people and set to music a bunch of times:

That the Russians have doubled down on their response to my projections and developed “Z” and “V” shaped spotlights—symbols that to Ukrainians are tantamount to swastikas—makes their response shocking and attention grabbing every time.

A good target, in short, is going to be one where people will immediately know why you are projecting that message on that building and thus that tells a specific and compelling story about a message being sent in given time and space. Think in the language of deadlines:

“Think tank scholar projects pro-Ukraine symbols on Russian diplomatic facility.”

“Bucha survivor tells her story in laser projection on Russian embassy.”

“Ukrainian teenager living alone in New York projects New Years greeting on Russian embassy.”

“Pro-Ukraine protestors taunt President Trump on the face of the Washington Monument, visible from White House, after Oval Office meeting with Ukrainian president.”

The ideal target, moreover, will somehow provoke a response. Remember that a story always works best when it has not mere action—what you did—but counter-action: what they did in reaction.

Having angelic children lay sunflowers at the gates of the Russian embassy is one thing. Having an irate Russian diplomat actually get out of his car to kick the sunflowers in a rage: That gets attention:

Planting sunflowers outside the embassy is a one-day story. The repeated destruction of those sunflowers by some mysterious force keeps it people’s minds.

It is the counteraction by the other side that shows impact. And it is in the interaction that lies drama.

So the first part of my how-to guide boils down to two things: First, the injunction to be highly experimental (just try it) and, second, a certain degree of guidance as to targeting: look for targets that are meaningful with respect to message and where a response is likely or can be provoked.

I’m going to address legalities of all of this in a separate post later on, but one word on legality in relation to target selection is in order: Different buildings implicate very different legal considerations. The Secret Service considers projections on embassies (which are the property of foreign governments) to be First Amendment protected activity. Projecting on an individual’s house is obviously a very different matter (don’t do it). I once projected on the Willard Hotel because the Iraqi prime minister was staying there and I was working with the family of Elizabeth Tsurkov, who is (still) being held hostage in Iraq, to put pressure on him to secure her freedom.

The Secret Service had no problem with it, but after the Willard complained to the DC police, the DC police did have a problem with it, the Willard being private property and all, so we worked with the Secret Service to project on a federal building visible from the hotel instead and everyone was happy.

The Capitol Police do not tolerate projections on congressional buildings at all. By contrast, many infrastructure installments (highway overpasses and the like) can make great targets and don’t raise any questions.

What you can get away, in other words, can be highly situationally dependent. And again, there is no way to find out what you can get away with other than to try and see what happens.

I will have more to say about the legalities later on in this series. For now, I’ll just say this: Many good projection protests raise no legal issues whatsoever, and many others may in theory but don’t in practice.

In the next post in this series, I will take on the question of equipment, talk about the pros and cons of different types of projectors, and make certain specific product recommendations for different applications and protests and conditions.

Friday on #DogShirtTV, the estimable Holly Berkley Fletcher and I had a serious discussion about what Lawfare content constitutes pornography for our core readership. It was weird as hell. We also talked about tariffs, Holly’s upcoming book, and Trump’s abuse of asylum seekers.

Friday On Lawfare

Compiled by the estimable Mary Ford

A Legal Standoff in the Lone Star State

Anna Bower parses the legal questions surrounding the ongoing political battle in Texas after 51 Texas House Democrats left the state on Aug. 3 to prevent Republican lawmakers’ efforts to redraw congressional maps—including whether Gov. Greg Abbott can remove absent Democrats from office.

In the days that followed, Texas House Speaker Dustin Burrows announced that he would sign civil arrest warrants for the absent Democrats. A sitting U.S. senator, John Cornyn (R-Texas), asked the FBI to assist Texas state law enforcement efforts to “locate or arrest” them. And Abbott made good on his promise to seek the removal of Democratic legislators, starting with a petition that asks the Supreme Court of Texas to remove the so-called “ringleader” of the effort, state Rep. Gene Wu, on grounds that he “abandoned” his office.

All of which has Americans fretting over several questions concerning Texas state law. Why exactly did the Democrats leave? Can they really be arrested? Can Gov. Abbott actually remove the Democrats from office? And what the heck is a “quo warranto” action, anyway?

Brokered Violence: Safety for Sale in the Free Marketplace of Data

Sam Adler, Thomas Kadri, and Chinmayi Sharma—in response to a string of attacks, including the murder of a Minnesota lawmaker in June—propose a new system to regulate data access and combat violence enabled by the sale of personal information by data brokers.

One of the most egregious shortcomings of these state and federal laws is that, by focusing solely on government actors, they do nothing to alleviate the unjust burden placed on other vulnerable groups. In addition, neither law establishes a centralized system for data removal, instead forcing people to navigate disparate takedown requests across hundreds of brokers. This feeds directly into the fractured landscape that produces so many of the secondary harms these laws were intended to prevent. It is questionable how much safety these provisions really provide.

Rethinking Immediacy in Israel’s Right of Self-Defense

Jeffrey A. Lovitky defends the legality of Israel’s attacks on Iran in June, arguing that legality can be ascertained by assessing the necessity and proportionality of the strikes, not the immediacy of their timing in relation to Iran’s 2024 attacks.

The passage of six months between Iran’s 2024 missile attacks and Israel’s resort to force on June 13 in no way extinguished Israel’s right to invoke those earlier attacks as the legal basis for the use of force in self-defense. That right remained operative, notwithstanding that direct hostilities between Iran and Israel had abated until Israel launched its attack in June. Once the right to self-defense attaches—that is, once a state has been subjected to an armed attack that triggers the lawful exercise of self-defense under Article 51 of the UN Charter—it does not expire merely because a significant amount of time passes before the state chooses to respond. The question is not whether Israel acted promptly following the 2024 attacks, but whether, as of June, Operation Rising Lion constituted a necessary response to a continuing threat.

Podcasts

On Lawfare Daily and Scaling Laws, Kevin Frazier sits down with Brian Fuller to discuss the challenges to creating policies that ensure that artificial intelligence technologies are safe, aligned, and socially beneficial.

Videos

On August 8 at 4 pm ET, I sat down with Bower, Roger Parloff, and Peter Harrell to discuss legal challenges to the president’s IEEPA tariffs, the legality of Immigrations and Customs Enforcement raids in Los Angeles given the temporary restraining order in place, and more.

Announcements

Lawfare is hiring a new fall editorial intern. The editorial intern will report to the associate editors. Responsibilities of the role include maintaining the Lawfare site, contributing research to support analysis of key issues, and more. Applications will be considered on a rolling basis. See how to apply here.

This fall marks 15 years of Lawfare, and we’re celebrating the only way we know how—by gathering our community of readers, listeners, and contributors for an evening of reflection, recognition, and a look ahead. The evening will feature some of your favorite Lawfare voices, a look back on the key moments that have shaped our first 15 years, and a sneak peek into what’s coming next. A reception will follow the program. RSVP here.

Today’s #BeastOfTheDay is the squirrel, seen here engaged in a traditional squirrel practice to beat the summer heat:

In honor of today’s Beast, be grateful for your AC.

The Cactus Collective Noun

We got some great suggestions for the appropriate collective noun for the proliferation of cacti. Since Substack only allows five options in a poll, I (EJ Wittes) have selected my five favorite suggestions. My decision in this matter is matter of my unreviewable discretion under my inherent constitutional authority. Congratulations to tupper, JB, Jeff , Marianna M., and M. Apodaca.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Dog Shirt Daily to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.