Kharkiv At War: A Photo Essay

A city out of fucks to give going on with life as abnormal

Good Afternoon:

I spent two days this week seeing the sights in Kharkiv—which is not a place most people go sightseeing.

My time in this large city near the front was a combination of meetings with civilians who live here and with military folks who are defending the city, on the one hand, and trudging through the bitter cold to see both how close the front-line came to Kharkiv in 2022 (right inside the city) and to understand the ongoing impact on the city of the war.

The current front line now runs about 50 km away, but the war—in a way that’s different from Kyiv or Odessa—intrudes constantly on daily life here.

To give you an idea of just how constantly, I made this screenshot video of roughly 24 hours worth of air raid alerts for Kharkiv.

The volume of these alerts is so overwhelming, that you either spend your whole life in a shelter or you start ignoring most of them pretty fast. The locals, at least in my experience, mostly seem to treat them as the background noise of their daily lives.

As the estimable Kate in Kharkiv—who blogs about life in Kharkiv on Twitter and Bluesky and for whom you should buy a coffee—explained to me, for the really dangerous attacks, you don’t get alerts anyway. Kharkiv is so close to the front that ballistic missiles reach it regularly before air alerts can sound. Your notification for those is when you hear the explosion, she said.

And you do hear explosions here. From a village just outside the city, you can hear the rumble of artillery from the front at times. There are jets that you can often hear but not quite see. And there are attacks—most of which don’t get through in any kind of lethal form but some of which do. Here’s a drone interception I saw the other day:

The war comes to Kyiv regularly, but it never leaves Kharkiv.

I honestly did not expect to fall in love with Ukraine’s second city. Kharkiv has a reputation as an old Soviet industrial town—a bit gritty, economically in need of development even before the war. Think Pittsburgh before its renaissance or Cleveland even after its renaissance.

The first thing to understand about Kharkiv is just now wrong this reputation is. Kharkiv is architecturally fascinating. There are mesmerizing examples of both tsarist-era and Soviet architecture—from all periods of the Soviet Union—densely packed in a city center that is just endlessly interesting. This is not Odesa, a city built around palaces and theaters and grand staircases. Think instead about some hybrid child of a 19th Century European city that mated with a textbook on Soviet architectural history and had cool post-Soviet redesign and modernization of countless buildings—all with old trolleys running through the streets. It would be a fabulous walking city—especially because of the quality of Ukrainian cafe culture—except for the bombing.

Kharkiv has been pervasively maimed by the war. In 2022, Russian troops tried to take the city; they shelled it brutally from the outskirts, and there were fierce battles close to the city center when teams of Russian soldiers tried to establish presences there. Much of the damage dates from then. But even now, the maiming goes on daily.

The air defenses for the city are good. I did not feel unsafe at any time during my stay there. But I was also staying in a hotel on the ground floor of a building surrounded by other high-rise buildings—a hotel carefully chosen for its protected locale in their lee—and I was staying in a room with no windows (windows are bad).

I was also chaperoned while taking the pictures that follow by military folks who know what they are doing and, throughout my trip to Kharkiv, by the most estimable Jimmy Rushton—a British freelance journalist and analyst who has lived in Ukraine since 2022 and whom you should follow)—who knows the city extremely well and knows what one can and cannot do safely. Here is my conversation with Jimmy from the other day on his work in Ukraine:

Of critical importance, Jimmy can navigate Kharkiv without GPS and its civilian interface, Google Maps. You can’t count on GPS in Kharkiv because the Ukrainian military jams it during air attacks to frustrate the navigation of incoming ordinance. There are also places in the area that are still mined. You don’t want to be in Khariv as a foreigner without professional help.

As with my earlier photo essay on Odesa, I am going to mostly let these images speak for themselves. Most of them require no explanation. In some cases, however, explanatory text helps illuminate things.

I shot these four images from a single location. Whether you are looking at a picturesque, modern European city or at a theater of active warfare can be a matter of which direction you are facing:

The number of downtown buildings in Kharkiv that have sustained damage is hard to overstate. The damage is on a spectrum—from a few windows being blown out by blasts nearby to total destruction and everything in between.

Let’s start with this block of major downtown buildings, all destroyed:

If you turn the corner and walk down the street, you’ll see that the buildings there are destroyed too:

Here are is a zoomed-in shot of the black building—and the one behind it—in the picture above. As you can see, the black “building” is actually a screen masking a former building, and the “building” in back of it is entirely boarded over:

Literally across the street from this scene of devastation is a fashionable cafe called 1654, where I met with Kate from Kharkiv (mentioned above). The scene in 1654 looks like this picture I snagged from Google Maps:

It’s a chic modern vibe with good food, coffee, and cocktails. You don’t feel like you’re in a war zone sitting in 1654.

Kate chose the spot, she told Jimmy and me, because of this view out of its window:

“It used to be a beautiful building,” she told us.

Indeed, Kharkiv is unlike Kyiv in that the percentage of downtown buildings that have some degree of damage can really overwhelm you. In Kyiv, the power situation and the heating situation are genuine disasters, and air attacks are a nightly affair; and there is no shortage of buildings that have been hit with drones or ballistic missiles. I don’t mean to dismiss the situation in Kyiv.

That said, the average building looks normal. The average street looks normal. The average neighborhood doesn’t look devastated. You can actually pretend you’re in a normal city in a Western country a lot of the time—if you don’t take off your coat and you’re in a building that has a generator.

Kharkiv is different:

Sometimes it’s just blown out windows from detonations nearby:

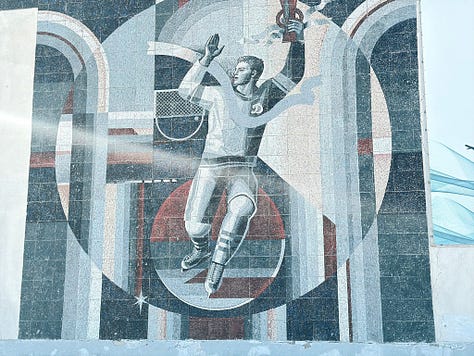

Sometimes it’s a lot more than that—like a sports complex completely destroyed with only old Soviet mosaics still surviving:

Or a school remarkably close to the center of town, where around 20 Russian soldiers holed up and refused to surrender during the attempt to take the city in 2022 and where a sign above the front entrance still cheerfully greets students in both Ukrainian and—incongruously—German—with the words, “Success in study is success in life!”

Sometimes it’s an iconic old piece of Soviet modernism, like the Derzhprom building, a 1928 complex that is known as the first Soviet skyscraper—bombed by Russia in 2024:

Or it’s a municipal administrative building that looks from the front like it is still standing:

And even looks okayish from the side:

But if you walk to street behind it you find out that the facade of mere damage is, well, a facade. The building is totally destroyed—as is the entire street behind it:

I could go on but you get the point.

The visuals associated with such destruction can depict compound disasters. Here, for example, are people gathering in front of one of the buildings featured earlier on a frigid morning at 7:00 am (and when I say frigid I mean below zero degrees Fahrenheit, which is around -20 degrees Celsius) from a water truck. They are here because they have no running water at home. Jimmy and I ran into this scene while waiting outside 1654 for it to open so we could have breakfast:

Even buildings that look unscathed have scars. From the outside, the Annunciation Cathedral looks pretty great:

Go inside, however, and the internal bleeding becomes apparent:

Then go across the street to what used to be a daycare center. The drone attack on this daycare center took place only a few months ago. The drone strike was actually caught on a CCTV video camera down the street, and Rushton tweeted that video of it at the time:

Here’s what the place looks like now:

The blast was so strong, that here’s what the building next door looks like now:

And here’s what the building across the street looks like now. Note the bend inward of the front face of what used to be window and door frames:

While I was taking pictures, Rushton actually found the CCTV camera that almost certainly took the above video:

I took a photo from the same angle; you can see the cathedral down the street:

A part of a bicycle that used to adorn the front face of the daycare center is now the only sign left that this used to be a place where kids played:

Speaking of kids playing, once you notice the remnants of childhood playthings in a city like Kharkiv, you start seeing them everywhere. Within a few hours of being in the city, I became particularly interested in taking pictures of playground equipment at sites of rocket and drone attacks. Here are some of them:

Outside of the city center, things are sometimes worse. I was privileged to be taken around Kharkiv by a military commander—let’s call him Andriy—who had participated in the defense of the city. He and his team took me to an area of apartment blocks that had faced particularly fierce Russian artillery shelling simply because they were between the Russian positions on the outskirts of the city and the center of the city. Here’s what that neighborhood looks like now. Some of the buildings, as you can see, are simply not there any more. All of the remaining buildings have significant damage. People are still living in them:

These images are of the village of Vil’khivka on the outskirts of the city. The village was occupied by the Russians, until Ukrainian forces liberated it later in 2022. Much of the village was destroyed in the fighting. Red flags designate no-go areas where there are still live mines:

Again, people are still live in this village. Note the Christmas tree ornaments hanging outside this house, which along with one or two others, appears miraculously undamaged given the scale of the destruction around them:

A lot of the damage to Kharkiv took place in 2022, in the early days of the full-scale war when the Russians tried to take the city and before the Ukrainians pushed them back. But not all of it. As I mentioned above, the destruction of the daycare center near the cathedral happened only in October. And an attack downtown that obliterated this building happened only two weeks ago—recently enough that laundry is still hanging in one portion of the building:

The war here remains close, and it remains ever-present. And the city requires ongoing defense, both in a macro sense and in countless micro senses, as a result.

So there are sandbags protecting the windows at a gas station, which—as you can see from the damage to the station—has good reason to have them stacked up by the windows. But the sandbags do make the gas station a relatively good spot to have a Zoom meeting next to a window:

Such defensive measures—public and private, simple and elaborate—are all over the place. The military has placed anti-drone netting over swaths of the ring road which encircles the city. While we were driving a lengthy stretch of this covered road, a truck in front of us carrying earth-moving equipment discovered the hard way that it was too tall. It began scraping the netting as it passed underneath, causing large amounts of ice to fall on the road. At one point, it even began tearing the netting and bending the polls that support it.

As this was happening, the woman who was translating for us on the excursion—whose name is Hanna Prokosheva and whom you should follow on Instagram—turned to me and said, “Let it snow. Let it snow. Let it snow.”

She later posted a version of the same joke to Instagram, along with the comment, “Humor and the ability to see beauty in sadness protect us in this reality.”

Over coffee a few hours later, I asked Andriy what he thought it was important for people outside the country to understand about life in Kharkiv. I’m paraphrasing his answer here—through Hanna's translation—so don’t take the following too literally. But please do take it seriously.

People need to understand that we are not leaving, he told me. There are a million and half people living in Kharkiv. We didn’t leave when the Russians were in town. We haven’t left while they’ve shelled us for four years. We are not going away.

It’s a city out of fucks to give, going on with life as abnormal.

These post cards are among my reasons for supporting Lawfare.

Thank you, Ben. You are a pretty estimable fellow yourself.

Although I read a lot and have a sense of the level of destruction that Russia is aiming at Ukraine, your photographs and commentary really moved me. I have great admiration for the tenacity and inventiveness of Ukrainians in their struggle for their freedom.