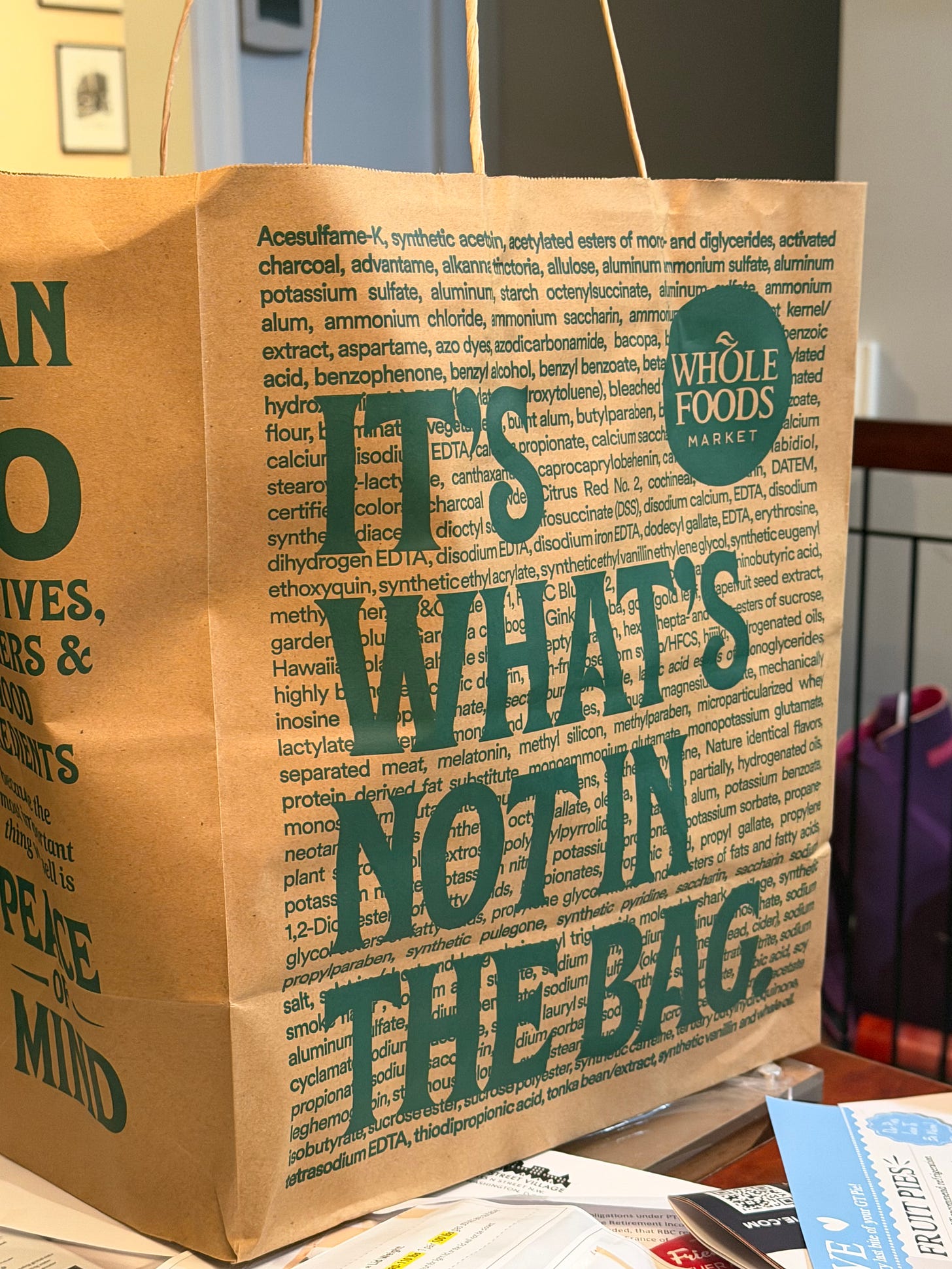

What's Not In the Bag

I smell a video in the making

Good Morning:

Perhaps I should make a “What’s Not In My Bag” video to go along with my “What’s In My Bag” video:

Think about it: There are so many options. A giraffe? Not in the bag. World peace? Not in the bag. Chupacabra? Justice? Both not in the bag.

There is comic potential here.

Operation Brahms

And it came to pass that we arrived at one of Brahms’s early chamber music masterpieces: the Opus 18 string sextet. I have known this piece well since I was a teenager, and it’s rolling around on the opus list is a good occasion to reflect on what makes Brahms chamber music distinctive.

Because this piece has all of the elements.

There are, first, the gorgeous, sinewy melodies. In this case, you hear one of them right at the opening of the first movement, but if you count them, there are actually a whole bunch throughout the piece. Brahms is one of history’s great melodist, and these melodies are remarkably complicated. They are long. These are not just a few bars that you can hum—though many of them are real earworms. It can actually sometimes be hard to figure out where one them ends and another begins. They are also carefully developed—often dancing between delicacy and frenzy.

There are, second, Eastern European-inflected themes. Brahms would, of course, later go on to write a set of Hungarian dances, and you can hear the influence of Austro-Hungarian Empire all over his music, though he was not yet living in Vienna at the time he wrote this piece. This tendency is already notable in this sextet. See, for example, the theme that opens the second movement—a stately andante that sounds somehow east of German.

Third, there is the almost superhuman control and discipline. I have emphasized this before, and I’m sure I will emphasize it again, but Brahms is writing in the era of Richard Wagner, who wrote dazzlingly long pieces in which one can drown if one isn’t careful, and Franz Liszt, who always favored displaying his own virtuosity as a pianist over the compositional perfection of the piece of music he was writing. Brahms is, I think, reacting against both these tendencies of his older contemporaries. He is not trying to create some kind of Gesamtkunstwerk (”total work of art”) here or to capture and define the German soul, nor is he trying to show off his players. He is trying to create nothing more or less than perfect beauty with six carefully chosen instruments. Brahms’s chamber music is almost perfectly controlled towards this end—the energy and emotionalism emanate from his profound commitment to form and structure.

All of these tendencies will grow more pronounced, but they are all maturely visible—or audible—in this sextet, played here by the Amaryllis Quartet, along with Volker Jacobsen on viola and Jens Peter Maintz on cello.

Friday on #DogShirtTV, the Greek Chorus and I had another rambling, revolutionary conversation, covering Chinese aggression towards Taiwan, US aggression towards Venezuela, and my aggression towards the Facebook advertising algorithm:

Today’s #BeastOfTheDay is the raccoon, seen here really regretting its life choices:

In honor of today’s Beast, when your friend says, “hey, you know what would be really funny?” just walk away.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Dog Shirt Daily to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.