What is an "Art Song"?

The discussion continues

Good Morning:

A sprite of mischief has done a mischievous thing in Arlington, Virginia—again. I hear there are a bunch of these signs in the neighborhood where White House Deputy Chief of Staff Stephen Miller lives.

Sprites of mischief are very much beloved by God.

Whether such sprites have anything do with the matter, Miller appears to feeling uncomfortable in the neighborhood these days and has put his house on the market. Reports ARL Now,

White House deputy chief of staff Stephen Miller is selling his Arlington home after it was repeatedly targeted by activists.

The nearly 6,000-square-foot house, custom built with interiors that “embrace a refined Southern California aesthetic,” is listed for $3.75 million. Located on a cul de sac adjacent to a park in a quiet northern Arlington neighborhood, it sold new in 2023 for $2.875 million, records show.

Miller, said to be “the architect of Trump’s hardline immigration policy,” is one of the administration’s most controversial figures. On at least two occasions this year, including most recently in mid-September, activists have written messages of protest in front of his house and in the nearby park.

“Stephen Miller is destroying democracy,” “stop the kidnapping,” we [love] immigrants,” “hate has no home in Arlington,” “no white nationalism,” and “trans rights are human rights” are among the chalk messages seen last month before being washed away.

The chalk messages were written just days after the assassination of Charlie Kirk in Utah, prompting Miller’s wife, the podcaster and former communications official Katie Miller, to post a message of defiance on social media.

“To the ‘Tolerant Left’ who spent their day trying to intimidate us in the house where we have three young children: We will not back down. We will not cower in fear. We will double down. Always, For Charlie,” she posted via X on Sept. 14, accompanied by a video of some messages being removed with a garden hose.

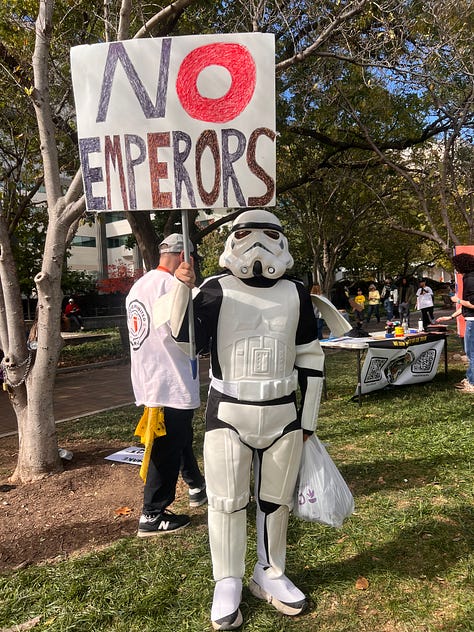

Speaking of sprites of mischief, this one showed up with a similar message at today’s No Kings rally in Washington. She was unaware that her sign was sporting the same message as that of sprites of mischief in his neighborhood or that Miller’s home was on the market. She also didn’t want her face photographed. But she appeared delighted to hear of the company she was keeping.

Here are some other cool signs I saw today:

Wednesday on #DogShirtTV, the estimable Carol Tsang showed up with a question: what is the President actually supposed to do? We discussed. We also discussed the death of Kenya’s opposition leader:

Thursday on #DogShirtTV, the estimable Laura Field came on the show to discuss her new book about the intellectual radicalization of the GOP and the various currents of thought behind Trumpism. Fascinating, scary shit:

Recently On Lawfare

Compiled by the estimable Isabel Arroyo.

‘Slaughter’-ing Humphrey’s Executor

Nick Bednar parses the legal questions raised by Trump v. Slaughter, which concerns President Trump’s effort to fire Federal Trade Commissioner Rebecca Slaughter without citing any of the causes required by statute. Bednar explains the stakes of this case, which could repudiate Humphrey’s Executor v. United States and empower presidents to more easily remove subordinates.

By the beginning of Trump’s second term, many legal scholars regarded Humphrey’s Executor as effectively on life support. That perception was reinforced when the Supreme Court stayed a district court order enjoining the removal of members of the Merit Systems Protection Board (MSPB) and the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB). In an unsigned, two-page opinion in Trump v. Wilcox, the Supreme Court concluded that “the Government [was] likely to show that both the NLRB and MSPB exercise considerable executive power.” The majority, however, stopped short of deciding whether those agencies fell within the Humphrey’s Executor exception. Nevertheless, it felt the need to recognize a new exception for the Federal Reserve—an agency not before the Court—reasoning that the “Federal Reserve is a uniquely structured, quasi-private entity that follows in the distinct historical tradition of the First and Second Banks of the United States.” Such an originalist-inspired carve-out would have been unnecessary if Humphrey’s Executor remained firmly intact.

Authoritarian Soft Power

Moises Naim reviews “Dictating the Agenda: The Authoritarian Resurgence in World Politics,” by Alexander Cooley and Alexander Dukalskis. Praising the book as “excellent,” Naim examines the authors’ account of how authoritarians export norms and narratives abroad, unpacks their model of “authoritarian snapback,” and considers where their approach might have benefited from reference to other disciplines.

The authors’ core insight is that authoritarian politics has gone transnational. Instead of merely resisting liberal interference, regimes from Moscow to Beijing to Ankara have learned to project influence outward—reframing legitimacy, rewriting rules, and manipulating the mechanisms of globalization to their own advantage. In this reading, the contemporary global contest is not just about territory or ideology; it is about who gets to decide what counts as normal.

Cooley and Dukalskis describe this process through what they call the “authoritarian snapback.” The concept captures a strategic progression: First, illiberal governments stigmatize liberal actors and ideas; then they shield their domestic publics from them; finally, they export their own narratives, norms, and incentives abroad. When successful, these maneuvers allow authoritarians not merely to parry liberal initiatives but to dictate the agenda—determining which issues are discussable, which words are acceptable, and which institutions can be trusted.

The Rule of Law and Major Questions Within Article III

Isaiah Ogren explains that lower courts’ blocking of the removal of executive branch agency members under Humphrey’s Executor despite Supreme Court approval of the removals does not constitute a rule-of-law crisis. Instead, Ogren argues that this friction between the courts should be understood as an intra-judicial power struggle conceptually similar to the dynamic between courts and Congress under the Major Questions Doctrine.

My point here is to assess neither the merits of any of these removals nor the overall performance of either the lower courts or the Supreme Court on the interim docket. Instead, I want to highlight similarities between the unfolding removal litigation and the major questions doctrine (MQD) and suggest that these parallels help us understand what is at stake in the removal cases. The conflict in Slaughter and associated cases is not about whether the Supreme Court or the lower courts are flouting the rule of law but, rather, about how costly it should be for the Supreme Court to change the law.

Russian Assets Redux: Examining New Proposals for Reparations Loans

Trent Buatte evaluates possible mechanisms for using Russian cash frozen in Europe to aid Ukraine without infringing the property rights of sovereign assets.

What may set the Russian sovereign assets apart, however, is their status within Euroclear. As with the ERA loans, the unique structure of Euroclear may make this sort of conversion easier, especially if ordered by the Council of the European Union. First, as with existing EU provisions on bail-ins, the council can order financial institutions to undertake conversions. That alone could give Euroclear legal cover. An ordered swap also ensures Euroclear’s assets and liabilities remain balanced since the cash deposits—which would normally be used to fulfill Euroclear’s obligation to pay out Russia—would be swapped for bonds of equivalent face value. Second, Ashley Deeks, Mitu Gulati, and Paul Stephan have also proposed that loans paid using Russia’s sovereign assets would not interfere in Russia’s property rights using the financial concept of set-off. Set-off is a commonly used financial action to settle (or net) symmetrical debts. In their proposal, loans issued using Russian sovereign assets could be set off against Russia’s reparations obligation to Ukraine without interfering with Russia’s sovereign immunity.

Podcasts

On Rational Security, Scott R. Anderson, Kate Klonick, Molly Roberts, and I discuss the first phase of the Trump administration’s peace plan for Gaza, messages on U.S. agency websites blaming the “radical Left” for the government shutdown, and China’s new export controls on rare earth metals.

On Wednesday’s Lawfare Daily, Mykhailo Soldatenko sits down with Serhii Plokhii to discuss Plokhii’s new book, “The Nuclear Age: An Epic Race for Arms, Power, and Survival.” The two discuss the role of fear and prestige in a country’s decision to acquire nuclear weapons, the strikes on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, preventative wars against nuclear aspirants, and Ukraine’s decision to give up nuclear weapons it inherited from the Soviet Union.

On Thursday’s Lawfare Daily, Michael Feinberg sits down with Jake Tapper to discuss Tapper’s new book, “Race Against Terror: Chasing an Al Qaeda Killer at the Dawn of the Forever War,” which chronicles the investigation, prosecution, and conviction of al-Qaeda operative Spin Ghul. The two discuss what Ghul’s case reveals about the American justice system post-9/11, the politics of counterterrorism, and how terrorism prosecutions have influenced national security policy.

“Art Song”

The estimable Richard Wattenbarger has at last provided his response to my use of the term “art song.” It begins with a lovely description of “Operation Brahms”:

On Dog Shirt Daily, the estimable Benjamin Wittes, has undertaken “Operation Brahms.” He’s listening to all of Brahms’s works in order of opus number from the beginning, the Piano Sonata in C major, op. 1, to the very end, the Eleven Chorale Preludes for organ, op. 122. And he’s doing it one of the best ways one can: by listening attentively and carefully to each piece along the way. Were he transported via time machine to late nineteenth-century Vienna, the locals—well, at least the musical Bildungsbürgertum—would affirm that, yes, this is the way this is done.

Wattenbarger then proceeds to give a concise procedural history of the dispute, one worthy of an appeals court judge:

Upon encountering Brahms’s 6 Songs (6 Gesänge), op. 3, Ben wrote a thoughtful post about these pieces. Along the way, however, he strayed from the straight path (“Nel mezzo del cammin?”) when, in a parenthetical aside, he referred to “the genre of Brahms songs (called ‘lieder’ [sic] by pretentious people who like to use German words to describe musical terms with perfectly good English words).” His father (whom I’ve not met but who, if his response is any indication, strikes me as a paragon of culture and good taste) responded to his wayward progeny by pointing out that Ben’s “sneering reference to the use of the word ‘lieder’ ignores the fact that the works traditionally termed ‘lieder’ are songs in which the texts that are set to music are themselves serious works of literature.”

Ben graciously accepted his father’s correction. Yet, once again, the specter of pretentiousness (and it’s only a specter) haunted Ben’s imagination, as he proceeded to write, “The term is sometimes translated into English with the even-more-pretentious term ‘art song,’ which is so terrible that sticking with the German is probably the least bad option.

Well, no.

It seems that my error was in confusing the word “art” in “art song” with art in the sense of the German word “kunst”:

In the history of Western music, we frequently deal with two different meanings of “art.”

The first of these meanings is related to the Latin ars, a word that refers to knowledge both about the world itself and how to do things in and with the world. When we use the term “art” in this sense, we usually have in mind the knowledge and skills that humans use to make things as well as the “made things”—artifacts—themselves.

The second meaning is the one that creates a problem. Some people who regard this sense as harboring an arbitrary judgment that certain artifacts are inherently superior to others. This meaning is also more recent. Historically, we associate it with the German word for the work of art, Kunstwerk, as the concept developed during what historians of Europe often call “the long nineteenth century.”

So what is an art song? As Wattenbarger’s very thoughtful explication describes, we should understand it as a song “intended for a context in which listeners are invited to, indeed, expected to reflect on the cultural artifact and its many meanings, and to connect it, historically, to other, older contexts of music-making and listening that can shine additional light upon the original.”

#YourMusicOfTheDay: Operation Brahms

Speaking of Operation Brahms, here’s today’s piece, Op. 11, Serenade No. 1 in D Major, the first of Brahms’s published orchestral works, a category which includes four symphonies, his two stunning piano concerti, and other important contributions. I have to confess, I am not sure I have ever liked a Brahms piece less than I do this one. I was not familiar with it before this project and was kind of excited about it. Color me disappointed. I have now listened to it several times hoping to be moved by it each time. I have listened to a few different performances. I even wrote to the estimable Richard Wattenbarger to ask if I was missing something and listened to this performance of it as his recommendation:

Color me unimpressed. If all Brahms were like this, I would not be the Brahms fanatic that I am. But what the heck. All the children cannot be above average. The whole thing sounds like Brahms making a mediocre attempt to sound like Beethoven to me. Also, it feels ponderously disorganized for Brahms to me.

My recommendation: Don’t let Serenade No. 1 be your introduction to Brahms’s orchestral music. Thumbs down.

Today’s #BeastOfTheDay is the rhinoceros, seen here squishing a gourd, but the real hero of this video is in fact the humble gourd, which we honor today for providing entertainment to numerous Beasts in the Oregon Zoo:

You can find many Beasts playing with many gourds here.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Dog Shirt Daily to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.