#SpecialMilitaryOperation: Berlin

And thoughts on the Supreme Court's denial of cert before judgment

Good Evening:

It’s an ugly building, and its proximity to the Brandenburg Gate—if you think about it in terms of the politics of divided Berlin—has a real dog pissing on a fire hydrant vibe.

The Soviets built their embassy to the defeated German Democratic Republic right up next to the grand monument of imperial Germany. It’s big, and it was meant to show who was boss.

I snapped a picture of it and threaded it:

The estimable Anne Applebaum quickly responded:

I love Berlin.

As I have aged, it has become one of my very favorite cities in the world. Like Istanbul and Jerusalem, it has layers and layers of history. Unlike such ancient cities, Berlin’s layers of history are almost entirely layers of 19th and 20th Century history.

I visited Berlin first in 1988, a year before the Berlin Wall came down. I hitchhiked my way there to a city that genuinely felt like a scene out of a John LeCarre novel. I went through Checkpoint Charlie. I walked along both sides of the wall—on one side of which was a modern Western city with a thick sense of irony and on the other side of which was a communist hellscape, a mixture of the worst of Soviet architecture and decrepit imperial buildings still pockmarked with bullet holes from World War II. The streets on one side had modern German cars. On the other side were the comical East German Trabants, which had not yet become beloved as weird kitsch.

It was the height of Glasnost but not in Berlin; the division there all felt very permanent. I never imagined the wall was a year from vanishing.

By the time I came back a little more than two years later, everything had changed. You could still mostly tell where the wall had been, a function largely of the difference in architectural style between the Soviet occupation zone and West Berlin. But the wall was gone, and the division—at least the visible division—was gone too.

I was in Berlin to sell a bicycle. I had been riding a bicycle all over New Zealand and, more recently, Scandinavia, and I was tired of riding and eager for a change of pace. And I had a hot commodity: an American touring bicycle of a type that was not sold in Europe at the time.

But there was a problem: my bicycle didn’t have “papers!” And no rule-respecting, rule-abiding German would dream of buying a used bicycle without “proof” that it was not stolen. It wasn’t that they didn’t believe me, of course. But rules are rules.

This is the part of the story in which I was introduced to the underground Berlin anarchist bike collective. These Germans didn’t follow the rules. They fixed bikes. They traded bikes. They didn’t pay full price for mine. But whatever, they helped me arrange to sell my bike to a buyer who was willing to wait for the proof of ownership a few months until I got back to Washington and could get a copy of the receipt from the store that had sold it to me.

I didn’t return to Berlin for the better part of 30 years.

When I did, it was—once again—a completely different city. This one was the capital of a united Germany. It had gleaming buildings and think tanks at which I spoke and fancy hotels at which I stayed. There was no hitchhiking. There were no anarchist bike collectives to help me semi-legally sell my means of transportation.

The Trabants had become a weirdly beloved bit of kitsch. Here’s one turned into a stretch limousine:

Three visits, three entirely different cities.

This time I was in Berlin for a very brief time—to do a projection and then fly home. But in my less-than-24-hours in Berlin, I met a bit of each of the three cities I had visited in years past.

As to old, divided Berlin, I was in town for a date with a relic of that period: the ugly Soviet building that still sits on the Unter den Linden, looming near the Brandenburg Gate. Dog. Fire hydrant.

The oppressive Soviet architecture actually offered some advantages for projecting. The compound means to be imposing, so it’s close up against the street, not set back far like the embassy in Washington. There also aren’t a lot of windows—the better to inscribe Soviet iconography in the concrete. And the building is dark. If you don’t turn and look at the vibrant street life that surrounds it, you can conjure 1988 LeCarre-era Berlin without too much difficulty.

I did my usual walk-by during daylight. An encampment of pro-Ukraine protesters, all of them German, sat in front of the embassy with a display on the ground. I approached them and asked whether they would still be there after dark. We got to talking about lights. I read them into my little scheme—about which they were excited.

And all of a sudden, I realized I was talking to a modern version of that evade-the-rules Berlin culture of the bike collective days.

One advised me (correctly, as it turned out) that the police would be slow to enforce any rules as long as I was just projecting on the wall and that I should, therefore, project until they made me stop. There was no chance of arrest. This same gentleman later arranged power for me from a nearby schwarma vendor, who was all to happy to help out. Another called a German television crew, which showed up to the film the whole thing.

I had been worried about what would happen when German rule-following culture met special military operations. I shouldn’t have been. Because with rule-following culture comes a certain rule-evasion sub-culture—the same subculture that helped me sell a bicycle thirty years ago.

And the Berlin police? Hats off to them. They were great.

They let me project for a full hour before coming over (they were standing across the street the whole time) and telling me if I didn’t shut it down, they would have to do so. I complied immediately, of course. They didn’t even look at my ID.

It was, all in all, one of the most moving #SpecialMilitaryOperations I have ever done. The street traffic was electrifying. We were right up close against a genuinely menacing symbol of authoritarianism in the middle of a free NATO country. In a particularly magical moment, a German passerby ran home to get his Ukrainian wife and bring her to see it. He then informed me that it was his birthday and it would be very moving for him if I would project “Putin Khuylo”—an obscenity that Ukrainians particularly love to see projected on Russian diplomatic facilities. I just happen to have it programmed on the laser for precisely such occasions.

The cops seemed unenthusiastic about my projecting on the Brandenburg Gate, and it was raining and cold anyway. So I packed up my gear. That third Berlin was beckoning—the one with a nice warm hotel I was staying at a few blocks away with a rather good restaurant I could never have afforded when I was hitchhiking and trying to sell bicycles. So I trundled back to the hotel and had an excellent meal and a way-too-large beer.

And I woke up the next morning at an unpleasantly early hour to fly home.

Here are some videos:

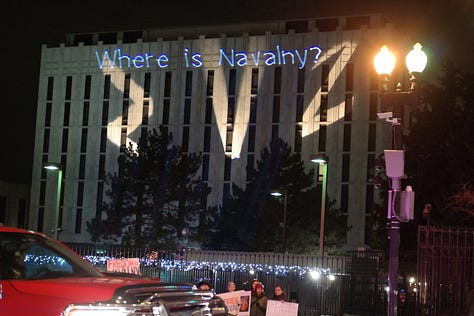

I had been back in Washington for a few days when I was approached by a lovely group of pro-democracy, anti-war Russians in Washington asking me to help them highlight the disappearance from prison of Alexei Navalny, which had happened a couple of weeks earlier. I was happy to oblige. The message was simple—in English and in Russian: “Where is Navalny?”

No answer from the embassy—except their disgusting “Z” and “V” spotlights, which seem like something of a non-sequitur in response to the question.

I was, however, very pleased to see Secretary of State Anthony Blinken raise the issue in public today:

The latest from Windsor Mann and Ruthie Windsor-Mann:

Today’s #BeastOfTheDay is this tiny chameleon, nominated by the estimable Holly Fletcher, who sends it in from the tip of her nephew’s thumb in Cape Town, South Africa.

Trump Trial Diary, December 23, 2023

The Supreme Court has declined Special Counsel Jack Smith’s petition for certiorari before judgment in the matter of former President Trump’s claim of presidential immunity in the Jan. 6 federal indictment.

As a reminder, this matter is important less because there is much chance that the Supreme Court will recognize the immunity that Trump claims than because deciding the question could eat up precious time.

Currently, trial is scheduled for March 4 in the U.S. district court in Washington DC. But the matter is on hold while Trump pursues this appeal.

The theory behind Smith’s move to get the Supreme Court involved quickly is that one appeal takes less time than two, and given that the Supreme Court is likely to be the decision-maker here anyway, there’s not a lot of reason to waste time at the D.C. Circuit.

So what does it mean that the Supreme Court has bucked this effort and basically told Smith to follow the regular order—an appeal to the D.C. Circuit and then an appeal to the Supreme Court afterwards if the high court chooses to hear it?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Dog Shirt Daily to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.