Chris Wray's Gift to Merrick Garland

What do you give an attorney general who has everything?

Good Evening:

What do you give an attorney general who has everything?

If you’re FBI Director Chris Wray, and the attorney general is Merrick Garland and it’s his going away event, you give him this tommy gun, of which I snapped a picture following its presentation this afternoon at the Justice Department’s Great Hall.

Garland seemed a little surprised.

Nobody has ever given me a tommy gun.

Just saying.

On a more serious note, Garland gave the following farewell address, which I commend to you. I found it moving.

It’s all subtext—but it’s pregnant with a very important message about career Justice Department officials, their oaths of office, and the norms of the department.

The key passages, in my view, are two. This one:

Each of us who comes to work at this Department begins our period of service with an oath. It is an oath that I have taken many times in my career, and an oath that I have administered to others many more times.

We swear that we will support and defend the Constitution of the United States and that we will bear true faith and allegiance to the same.

But bearing true faith and allegiance to the Constitution is not the end of our obligation. It is just the beginning.

It is just the beginning because, as Attorney General Robert Jackson warned in this very hall 85 years ago, the same powers that enable the federal prosecutor to pursue justice also create the potential for grave injustice.

Although our Constitution and laws include important constraints on law enforcement, they nonetheless grant law enforcement considerable discretion to determine when, whom, how, and even whether to investigate or prosecute for apparent violations of federal criminal law.

To ensure fairness in the administration of justice, we must temper this grant of discretion with a set of principles that ensure we exercise our authority in a just fashion.

We must understand that there is a difference between what we can do — and what we should do.

That is where our norms come in.

Developed in the wake of the Watergate scandal, and formalized over almost half a century, those norms are our commitment to constrain our own discretion – so that our agents will begin investigations only when there is proper predication; and so that our prosecutors will bring charges only when we conclude that a jury will convict beyond a reasonable doubt and that the conviction will be upheld on appeal.

In short, that we will make our law enforcement decisions based only on the facts and the law.

Our norms are a promise to treat like cases alike — that we will not have one rule for the powerful and another for the powerless, one rule for friends and another for foes.

They are a promise to ensure respect for the integrity of our career agents, lawyers, and staff, who are the institutional backbone and the historical memory of this Department.

They are a promise to ensure protections for journalists in law enforcement [investigations], because a free press is essential to our democracy.

Those norms include our commitment to guaranteeing the independence of the Justice Department from both the White House and the Congress concerning law enforcement investigations and prosecutions.

We make that commitment not because independence is necessarily constitutionally required, but because it is the only way to ensure that our law enforcement decisions are free from partisan influence.

We know that only an independent Justice Department can protect the safety and civil rights of everyone in our country.

And we know that only an independent Justice Department can ensure that the facts and law alone will determine whether a person is investigated or prosecuted.

Those norms have been woven into the DNA of generations of DOJ employees, career and noncareer alike.

They are the commitments that ensure we will adhere not only to the letter of the law, but to the rule of law.

It is the obligation of each of us to follow our norms not only when it is easy, but also when it is hard — especially when it is hard.

It is the obligation of each of us to adhere to our norms even when — and especially when — the circumstances we face are not normal.

And it is the obligation of the Attorney General to insist on those norms as the principles upon which this Department operates.

It is the obligation of the Attorney General to make clear that the only way for the Justice Department to do the right thing is to do it the right way. That unjust means cannot achieve just ends.

The Attorney General must ensure that this Department seeks justice, only with justice.

And, critically, it is the obligation of the Attorney General to understand that the Attorney General is only a temporary steward of this Department, and that its heart and soul is its career workforce.

And this one:

I know that you do not do this work for public recognition — you do this work because you are public servants.

But I also know that a lot has been said about this Department by people outside of it — about what your job is, and what it is not, and about why you do your work the way you do it.

I know that, over the years, some have criticized the Department, saying that it has allowed politics to influence its decision-making. That criticism often comes from people with political views opposite from one another, each making the exact opposite points about the same set of facts.

I know that you have faced unfounded attacks simply for doing your jobs, at the very same time you have risked your lives to protect our country from a range of foreign and domestic threats.

But the story that has been told by some outside of this building about what has happened inside of it is wrong.

You have worked to pursue justice — not politics.

That is the truth.

And nothing can change it.

I know that a lot is being asked of you right now.

All I ask of you is to remember who you are, and why you came to work here in the first place.

You are public servants and patriots who swore an oath to support and defend the Constitution.

You are professionals of the utmost integrity who are worthy of the trust of the American people.

Your job is to do what is right, nothing more and nothing less.

I will have more to say about Garland’s farewell event tomorrow in my Lawfare column.

Today on #DogShirtTV, I welcomed the estimable Roger Parloff and the equally estimable Marty Lederman to talk over Vol. 1 of the Jack Smith report with me.

The cactus did not show up today. Today was all business.

We covered the ongoing shenanigans before Judge Aileen Cannon about Vol. 2 of the report, which has not been released, along with a variety of matters contained in Vol. 1, which has:

Today On Lawfare

Are CFIUS Decisions Legally Vulnerable?

James Brower and Nicholas Weigel outline legal challenges investors may raise against the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States, posing new tests to its jurisdiction, administrative procedures, and enforcement powers:

Although some actions are insulated from judicial review—such as the president’s decision to suspend or prohibit a transaction—several avenues exist to challenge decisions on constitutional and statutory grounds. CFIUS is likely to see its authority tested in the coming years as it asserts its jurisdiction over more types of transactions, pursues more aggressive actions on transaction parties, and imposes significant penalties publicly naming offending parties—actions that shift the calculus on when and how to challenge CFIUS in court.

AI Will Write Complex Laws

Nathan Sanders and Bruce Schneier argue that increasing pressure to write more detailed laws—driven by the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn the Chevron doctrine and political polarization— means Congress will increasingly turn to AI to draft laws, concentrating more power in the legislature:

Regardless of what anyone thinks of any of this, regardless of whether it will be a net positive or a net negative, AI-made legislation is coming—the growing complexity of policy demands it. It doesn’t require any changes in legislative procedures or agreement from any rules committee. All it takes is for one legislative assistant, or lobbyist, to fire up a chatbot and ask it to create a draft. When legislators voted on that Brazilian bill in 2023, they didn’t know it was AI-written; the use of ChatGPT was undisclosed. And even if they had known, it’s not clear it would have made a difference. In the future, as in the past, we won’t always know which laws will have good impacts and which will have bad effects, regardless of the words on the page, or who (or what) wrote them.

Podcasts

It’s a big day for podcasts on Lawfare.

On Lawfare Daily, I speak to Tyler McBrien, Anna Bower, and Scott Anderson about the second day of confirmation hearings for president-elect Donald Trump’s cabinet. We discuss hearings for Pam Bondi’s nomination to be attorney general, John Ratcliffe’s nomination to be CIA director, and Marco Rubio’s nomination to be secretary of state:

On Rational Security, Anderson sits down with Roger Parloff, Renée DiResta, and Tyler McBrien to discuss major national security news from the past week. They talk about the coming end of legal cases against Trump, corporate America’s shift to the right, and Trump’s threats to take control of Greenland and the Panama Canal:

Caroline Cornett shares the audio from Bondi’s confirmation hearing in front of the Senate Judiciary Committee on Jan. 15:

Olivia Manes shares the audio from Ratcliffe’s confirmation hearing in front of the Senate Intelligence Committee on Jan. 15:

Anna Hickey shares the audio from Rubio’s confirmation hearing in front of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on Jan. 15:

Tell Me Something Interesting

Where did the word “ceasefire” come from, anyway? The etymology is sort of obvious, of course, but a century ago, we would have called it an armistice, or a truce. Why ceasefire? EJ Wittes—drawn ever further into sin by the Oxford English Dictionary—investigates.

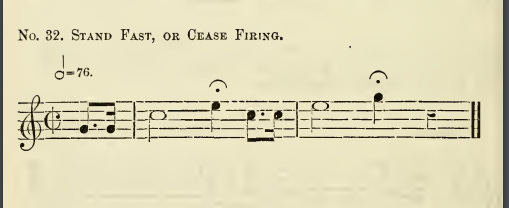

Bugles. The answer is bugles. See, the term “ceasefire” originates as a full sentence, an order—Cease fire—meaning, “Stop shooting your guns.” And the way that the British army in the 18th, 19th, and early 20th century communicated orders like “Cease fire” was with specific bugle calls. Here’s the “Cease fire” call:

You can find an archive of recordings of British regimental bugle calls here, and the full 1914 official sheet music here, if you need either of those for any reason. I can’t really think why you would, but I didn’t think I’d need them until about an hour ago, so who knows?

The usage of the term “cease fire” to mean a truce was originally a self-conscious metaphor. “Calling the cease fire” meant literally that: letting out the bugle call that meant “stop shooting.” It makes sense, therefore, that the OED credits the first usage of the modern sense of the term—a truce—to November 12, 1918, which you may recognize as the day after Armistice Day. “The ‘Cease fire’ of yesterday must be final and universal,” wrote the Times of London, clearly using the term in allusion to the bugle call, but omitting the explicit reference, in the expectation that readers would know what the writers meant.

But, as specific metaphors are repeated again and again, they stop being parsed as references and start being just regular words. (Consider, for instance, how the word “utopia” began life as a book title.) It can be hard to figure out when something crosses the line from reference to ordinary word, but the Google Ngram tool lets us cheat in this case. See, “cease fire” as allusion to a bugle call is written as two words, and cannot, grammatically speaking, take an indefinite article. So any usage of the phrase “a ceasefire” indicates that the term is being used as a recognized compound noun. Comparing the usage frequency for “cease fire” and “a ceasefire” over time, therefore, lets us see when the word ceasefire became definitively established.

We see here that “cease fire” becomes more common between 1930 and 1950, as the metaphorical usage took off. In response to that popularity, the compound word “ceasefire” begins to appear around 1940, and gains popularity much more rapidly, as people familiar with the metaphorical usage start to parse the term instead as a compound noun. By 1970, the compound overtakes the metaphorical usage entirely, giving us our modern term.

So, if you ever find yourself at some public gathering celebrating or demanding a ceasefire, now you know what instrument to bring and what music to play on it. You could also try playing it at British troops, if they’re shooting at you for some reason. I don’t know if that would work, but if you’re already getting shot at, you may as well try.

Today’s #BeastOfTheDay is the wolf, specifically these four wolves doing furious battle over a single apple. Truly, Eris lives on, and the Trojan War will be fought anew amongst the lupine community.

In honor of today’s Beast, wait until your friend is enjoying a snack, then bite the top of you’re friend’s head. Just do it. We promise this will have no long-term repercussions. Why else would God have given you teeth?

Video by Tanja Askani

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Dog Shirt Daily to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.